Pressing Matters is a group exhibition featuring 24 artists from Indonesia, brought together by artist Kevin van Braak. Split up into three interconnected parts, the exhibition addresses pressing socio-political issues in Indonesia. The exhibition space was transformed into a printing workshop, focusing specifically on local collective practices, mutual exchange, activism, and the boundaries and overlaps between art and craft

Pressing Matters has its origins in a long term project by Kevin van Braak, which departed from a research into the personal history of his Indonesian grandfather. The series of works that resulted from this project created a visual representation of his grandfather’s history, but his research simultaneously led to an increased engagement of Van Braak with contemporary issues in Indonesia, often relating to colonial history.

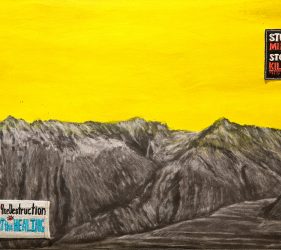

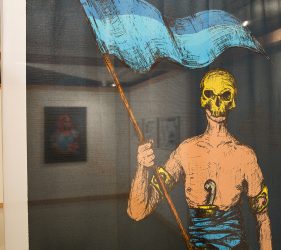

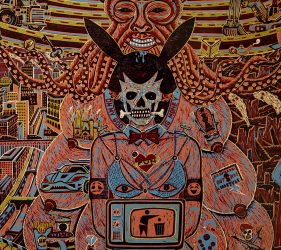

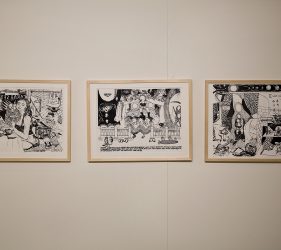

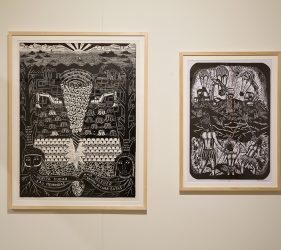

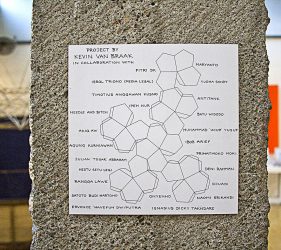

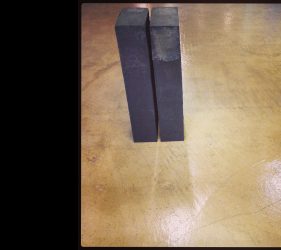

In a later artist-in-residency at Cemeti – Institute for Art and Society in Yogyakarta, Van Braak expanded the scope of his project to include other personal stories and histories, drawing from an intensive collaboration with local contemporary artists, writers, woodcarvers and activists. This resulted in the work Pentagonal Icositetrahedron (2017), the starting point of the exhibition: a three-dimensional spherical object with 24 sides, each carved design contributed by a different artist. Like a prism, the sphere reflects varying personal, activist statements, that not only overlap but also literally form one whole. Recurring themes are the exploitation of nature and natural resources, industrialisation and land rights, for example in the work of Fitri DK, Ervance ‘Havefun’ Dwiputra, Maryanto and Yudha Sandy. But topics of feminism and LGBTQ-discrimination are also raised, in the work of Ipeh Nur and that of activist collective Needle and Bitch. References to the history of Indonesia and the colonial past play a role in the work of Muhammad ‘Ucup’ Yusuf and Hestu Setu Legi. Special attention is given to the painful history of West Papua, for instance in the work of Papuan painter Ignasius Dicky Takndare, who will also be present for the public program of the exhibition. Over half of the participating artists, moreover, created new work especially for the exhibition, which for the most part address this specific theme. Artist Ipeh Nur (1993, Yogyakarta) was invited to the Netherlands in the weeks leading up to the opening, to create a new site-specific work for the exhibition in the downstairs hallway of the Tolhuistuin.

The sphere, combined with the wooden framework as well designed by Van Braak and modelled after a Javanese Joglo-house, is emblematic of the format of the exhibition; a social platform encouraging interaction and exchange. As a printing block, the sphere changes the space in a workshop: during the course of the exhibition, the 24 designs are printed, dried and freely distributed among the audience. By emphasising the craftmanship, and stressing the importance of widely spreading the activist messages, the exhibition challenges dominant definitions of art, in which scarcity and demand determine its definition and value.

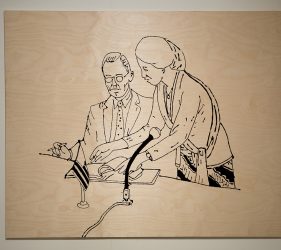

With Pressing Matters Kevin van Braak and Framer Framed create a collaborative space in which multiple conventions in the art world are questioned. Van Braak chose a working format in which the ‘collective’ takes centre stage, and hierarchy is avoided where possible, both in working with the artists as well as with Framer Framed: in the intensive collaboration process, positions and roles like artist, curator, producer and writer were not set in stone, but were taken on in a collective manner.

Participating artists

Kevin van Braak, Akiq AW, Antitank, Ibob Arief, Djuwadi, Fitri DK, Ervance ‘Havefun’ Dwiputra, Satoto Budi Hartono, Agung Kurniawan, Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Rangga Lawe, Hestu Setu Legi, Maryanto, Prihatmoko Moki, Needle and Bitch, Ipeh Nur, Onyenho, Deni Rahman,Yudha Sandy, Naomi Srikandi, Ignasius Dicky Takndare, Julian Abraham ‘Togar’, Isrol Triono (Media Legal), Bayu Widodo, Muhammad ‘Ucup’ Yusuf.

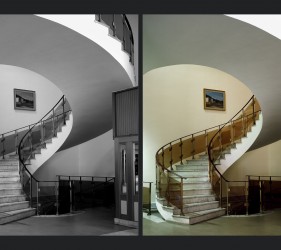

Installation photo ‘Pressing Matters’ at Framer Framed (c) Maarten van Haaff