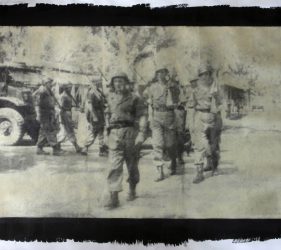

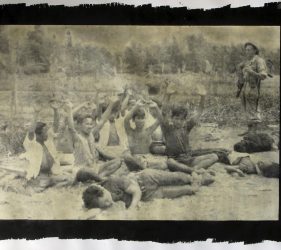

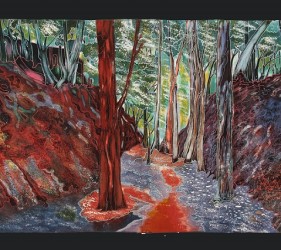

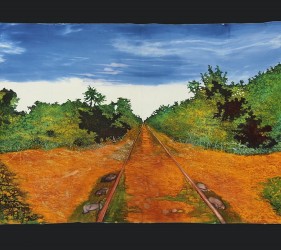

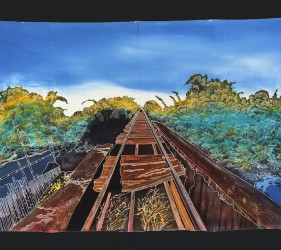

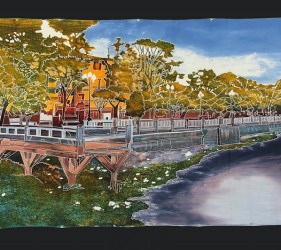

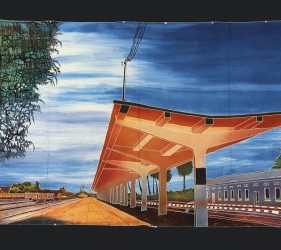

A few years ago, I initiated a project that focused on tracing the personal history of my Indonesian grandfather and his imprisonment by the Japanese during the Second World War and his role in Dutch colonial history during the infamous police actions (Dutch: Politionele Acties). I did extensive archival research, interviewed survivors and their relatives and traveled in the footsteps of my grandfather to Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia. Meanwhile, I have made several works, including various sculptures, a video, a film and a Wajang Kulit performance. In my solo exhibition Jejak Sang Kakek, Too many shadows, in Sismógrafo (Porto, 2015), I included a first series of colored batiks. These are based on photographs I took of the places central to my grandfather’s war past and that I visited 70 years later. I translated the photos into batik, since batik is a traditional Indonesian technique. The photos show places of suffering: places in camps, on railways, at a pier in ports where PoW were shipped. A second series of batiks on silk and paper followed. This time in black and white and showing the situation in Indonesia after WW II. They are depictions of crimes and events in which it is unclear what happens or has happened and that took place during the infamous police actions. The images were chosen from original photographs, which I found in national archives and in private collections. I opted for this turbulent time, because the role of my grandfather during these actions as ‘secret’ agent of the Dutch Navy (VDMB) remained largely unclear. I could only rely on anecdotes resulting in a vague and ambivalent image of his activities. I illustrated that ambiguity by highlighting the crimes on both sides, but in my choice (a selection of 18 photos from hundreds) it is not always clear exactly which direction we are looking at or what is actually taking place. The images consist of pixels, as in old newspaper photographs, and the papers are sizeable (each piece is 1.50 x 2,50 m). The large format forces you to distance yourself in order to see the image distinctly. It reflects the idea, researched in earlier work, that the general historical lines are clear, but as we zoom in and try to focus on details the (historical) image fades. In order to get the desired effect, I developed a batik technique that prints with wax. This allows to do batik in a photographic way, as it were, by taking the photo pixels as a starting point. A nice detail is that the word batik probably comes from the Javanese word titik that means dot. I transferred the wax technique that was originally executed on silk, to paper on which the wax was printed like a grid of dots of different sizes, making up the light parts of the photograph. The wax is then absorbed by the paper. Next, Indian ink is applied, that gets absorbed by the parts without wax and fills up the dark parts of the photograph.

In old photographs, we cannot determine the visible details of the image when we zoom in on it. Taking distance to become aware of something is necessary, but paradoxically enough, the details get blurry. It is the eternal problem of historical time. Here, the grid of historical fragments can only be supported (literally) by the distance the medium enforces to form a recognizable image.

In 1942, during World War II, Japanese troops invaded the former British colony Burma, now Myanmar. The new occupiers decided to rescue the old project to unite this country with Thailand through a railway, an idea that was meanwhile abandoned due to the difficulties posed by the route: a rugged terrain, punctuated by many rivers.

The enterprise that then happened – the building was completed in October 1943, sixteen months after they snatched the works – was done with the effort of 330 thousand men, among whom more than 60 thousand Allied prisoners of war (Dutch, English, Australian, etc.). The consequences of this work were tragic, more than 100 thousand people died, mostly due to mistreatment, working conditions, disease and hunger.

This infamous episode in the history of humanity intersects with the life of Hie Thwan Tan, born in Probolinggo, Indonesia, in 1917. In 1942, the Japanese army invaded the then Dutch East Indies, making countless prisoners, among whom was this policeman, who was taken by boat from Surabaya to Singapore, having afterwards been directed to the construction of theBurma railway.

Hie Thwan Tan was one of the survivors and is the grandfather of the Dutch artist Kevin van Braak, who in January 2013, decided to start a new art project, the most autobiographical to date, through which he would seek to recover not only thememory of facts that happened in World War II, but also fill silences related to his family history. This research has taken the artist on several trips to Southeast Asia – Thailand, Singapore, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia –, the consultation of archives, interviews and a Buddhist ceremony, culminating in the production of a shadow puppet performance (Wayang Kulit), about two months ago.

“Too Many Shadows” is the title of the exhibition by Kevin van Braak, which opens next Friday, October 24th, at 10pm, at Sismógrafo. The installation is comprised of painting, sculpture, video and a shadow play with dozens of characters. The show, produced mostly in Bali and curated by Óscar Faria, translates the research undertaken by the artist, and can be read either as an attempt to approach the histories of colonialism and the occupation in Southeast Asia, either as a ransom of memories where intimacy intersects with a public sphere maintained at the expense of simulacra and concealments.

The following week, on saturday the 1st of November, at 10pm, it will be presented “In memory of our ancestors, a musical event”, with the participation of Ensemble Gamelan Casa da Música, and the handcrafted musical instruments of João Pais Filipe (gongs) and Sonoscopia (keyboard percussion). In the final day of the exhibition, sunday November 16 at 6pm, it will take place a talk with Kevin van Braak and a screening of his film“Jejak Sang Kakek”, a record of the shadow theatre performance produced by the artist and presented in Bali.

City Lights

Since 2007 I archived money found on the streets of various cities evaluating not just economical, but class/social themes of a given area, in addition to chance.

The project started in 2007 in New York after finding over 150 coins and $60 in bills. Other cities include are Rome, Seoul, Berlin, Havana, Paris, London, Amsterdam, Antwerp, Florence, Bali, Phnom Penh etc…

The coins are presented in boxes with the name of the location and the dates of the findings.

In 2012 I started photographing each coin or banknote in it’s location up to now there are over 250 images

Batik

The 11 Batik paintings are part of the project Jejak Sang Kakek.

The images represent locations I visited during my trip while following the footsteps of my grandfather during the second world war when he was taken as a prisoner by the Japanese.

The images are the locations along the Burma -Siam railway, the railway he passed in Cambodia and the train station of Phnom Penh, the first location where he entered Vietnam and the last location where he was when the war ended.

Books for Burning?

In summer 2008 the first Fonds BKVB residency hosted by the Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, invited Kevin van Braak and Rossella Biscotti to spend three months in Lithuania to develop new work.

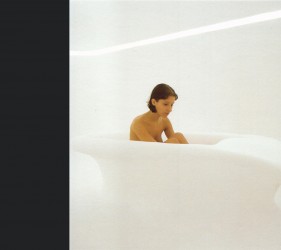

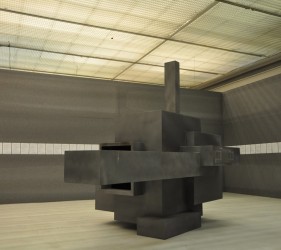

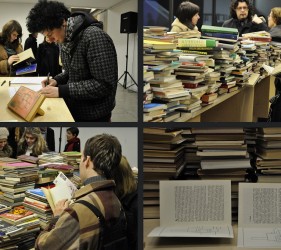

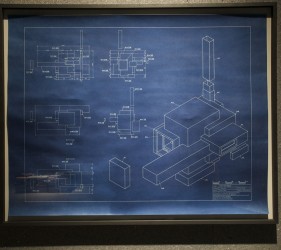

During the residency, the I developed a multi-functioning fire-powered oven. Built to specifications that result in an evocative blocky form, reminiscent of Constructivist Futurist tendencies of power/direction/movement, the oven is made of steel with different compartments for different purposes. On top of one of the many interlocking rectangular planes is a hotplate to grill food, encased in another water is boiled, its steam siphoned off to heat vegetables, different compartments for baking sit within the miniature factory and a hot tub is heated by the same fire. There is no single focal point to the oven as its activity is dispersed and five people are needed to operate it – from stoking the fire to tending the various cooking and leisure pursuits.

The environment created by the oven with its sculptural form and fruits of its function, is one of enjoyment and activity. This production is made more poignant when considering its is all being fuelled by books.

History is made of different shades of grey

The ongoing project currently consists of the reconstructed office desks of the controversial former world leaders – Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Tito, Mussolini and Nixon (Suhato in Production) – and the world globe that Hitler had in his office in the Reichskanzlei (the Reich Chancellery).

The desks and the globe are detailed, but are not exact copies. They have the original proportions, but are realized in a different material. The desks are coated in polyurea, which gives them a thick, grey rubber-like layer. It creates a unifying effect. Though the desks carry all the original details, these details are pushed into the background because of the uniform colour and coating. In that way, the desks act more as sculptures than as functional objects. Placed together in one room the exhibition has a height of 78 centimetres, which enhances even more a neutralizing effect. Yet, to neutralize what happened at these desks is not Van Braak’s intention. On the contrary, because of their similar outlook the history that was literally written at these desks comes strongly to the fore. Not in a literal sense or in a direct line with history. The new appearance of these historical objects makes that they resist being literally inscribed with decisions of life and death of millions of people, signed on these desks by their owners. Still, you cannot get rid of associating the thing with the harsh reality its original supported and the bitter imprint it leaves behind. For sure, the lumpy coating layer does not cover up the gruesome effects of some of the decisions made on these desks. It makes the lead globe on his steel support in the other room even heavier. Van Braak made this Columbus Grossglobus für Staats- und Wirtschaftsführer (Columbus’ Big Globe for World- and Economic Leaders) out of lead. Although it is immediately recognized as a globe, there are no countries visible on it. It evokes a story about Hitler having a small globe on his desk on which all the countries in the world were shown in one grey shade and overwritten with the word ‘Deutschland’ (Germany).